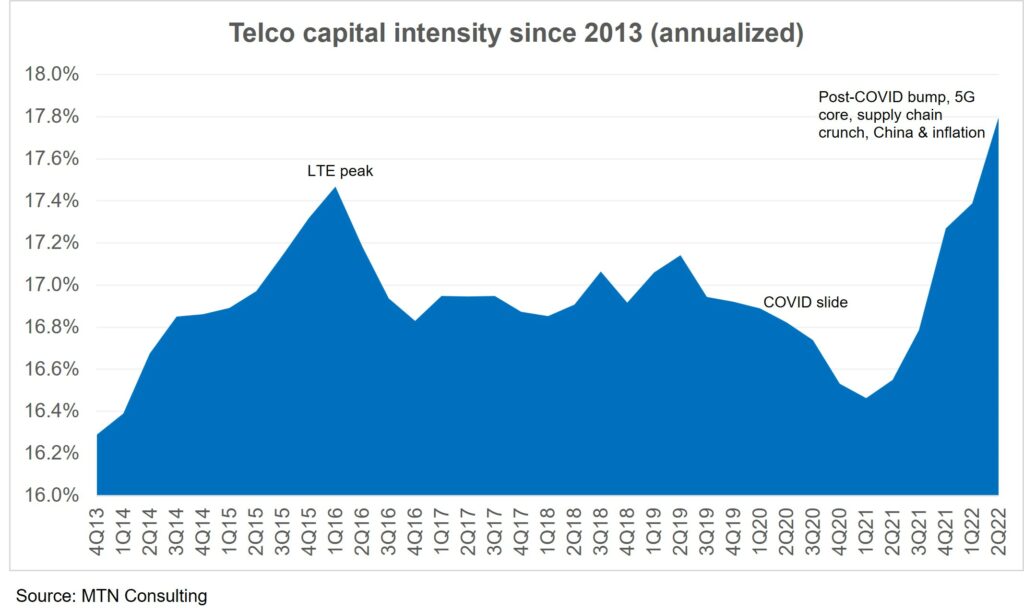

Vendors continue to wrestle with supply chain constraints in the telecom sector. That’s clear from several recent vendor earnings reports, including those issued by Dell, HPE, and Ciena in recent weeks. Telco spending, though, has surged in recent quarters. With 2Q22 results now compiled, the industry has reached a new capex peak. For the 12 months ended June 2022, telco capex was $329.5 billion (B), while the ratio of capex to revenues (i.e. capital intensity) was 17.8%. Both figures represent new record highs, at least for the 46 quarter (11.5 year) period that MTN Consulting data covers (1Q11-2Q22).

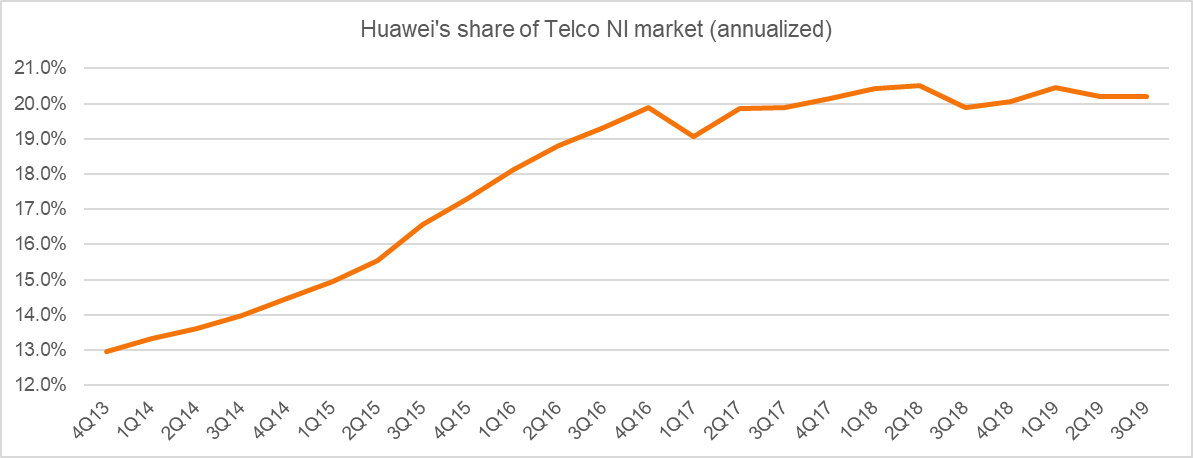

On the supply side, vendors selling into the telco vertical are seeing some growth, in aggregate. For the broadly defined “telco network infrastructure” (telco NI) market, revenues were $60.1B in 2Q22 (up 4.1% YoY), or $237.6B on an annualized basis, up 6.7% YoY. The telco NI market includes some vendor revenue streams which dip into telco opex, not capex, but there is usually a correlation between total capex and vendor revenues.

The figure below illustrates telco capital intensity over the last several years.

What’s behind recent capex growth

One factor behind the recent capex spending spike is a post-COVID bump. Economies shutdown during COVID, depressing network spend. The capital intensity effect is shown in the figure, above (“COVID slide”). Capex also dropped in absolute terms. Annualized capex bottomed out at $299.8B in 2Q20. Some of the current growth is just making up for lost time. The quarterly average hasn’t changed much, if you expand the time horizon. For the last ten quarters, from 1Q20 (the onset of COVID) through 2Q22, telco capex averaged out to about $77.9B per quarter. For the ten pre-COVID quarters, the average was $78.5B.

Another factor is many telcos are scaling up initially small 5G deployments, and beginning to build out 5G SA core networks. 5G RAN builds have been underway for several years, but the spending has been small to start due both to the software-centric nature of 5G networks and telcos’ desire to wait for new revenue models to emerge. Incidentally, a shift to 5G core spending tends to benefit a different type of vendor – not just the Ericssons and Nokias of the world. Cloud providers AWS, Azure and GCP, for instance, are all actively involved in helping telcos with 5G core migrations. Their collective revenues in the telco vertical were about $3.4B for the 12 months ended June 2022, up nearly 80% YoY. Many of the vendors involved in this are less vulnerable to supply chain issues.

Another capex plus: fiber spending is strong in a number of markets, especially the US but also in Europe, Australia, China, and India. That’s to support FTTx deployments but also to connect together all the new radio infrastructure needed to support 5G. Government subsidies and other investment incentives are a factor as well. Vendors focused on fiber optics are seeing strong growth right now. For instance, Corning and Clearfield saw their telco vertical revenues grow by 25% and 84% YoY in 2Q22, respectively.

Supply chain limitations have a mixed effect. They sometimes mean delay or cancellation of projects, which cuts capex in the short term. They also can mean price increases, though, as telcos push suppliers to accelerate timelines or adjust designs to work with available alternatives. This can result in projects costing more than expected. Let’s not forget, though, that a huge portion of telco spend is unaffected by current supply chain constraints. Services- and software- focused vendors – like Accenture, Amdocs, IBM, Infosys, TCS and Tech Mahindra – are not citing supply chain issues as a drag on results.

Inflation is a bit more straightforward. This has impacted the entire telecom food chain, from chips to components to systems to services. All else equal it causes an increase in US$ capex, though the impact on capital intensity is less clear.

Finally, there’s China. Given how closed a market this is, there’s not as much attention paid to it nowadays. But China’s capex has been growing recently. For the 2Q22 annualized period, Chinese telco capex totaled $58.3B, up 12% from 2Q21. That growth comes despite efforts to share costs on the network side.

China is also relevant to the vendor share question. Huawei continues to rank at the top of the global telco network infrastructure (telco NI) market. For the 2Q22 annualized period, we estimate its telco NI share at 18.7%, far ahead of Ericsson (10.9%) and Nokia (8.9%). This surprises some, as Huawei has become a non-factor in many markets over the last two years. Yet Huawei’s stability is no mystery. It’s dominant at home, and local telcos have been spending big, and steering more of their capex dollars to local suppliers over the last couple of years. Huawei also has a huge customer list overseas – these revenue streams don’t just disappear overnight, especially since many telcos remain loyal to the vendor.

Hardware hit hardest in supply chain crunch

Vendors recorded about $237.6B in sales to the telco vertical for the 2Q22 annualized period. This is a huge market, with many different players; MTN Consulting stats track 132. Some supply the latest and greatest hardware innovations. They often have high margins but can also be subject to supply chain hiccups. Vendors specializing in solutions which revolve more around software and/or services tend to have different constraints. Labor cost and availability is always a concern, but hardware is rarely an issue. We believe the current supply chain disruptions will improve in the next couple of quarters, though. Even those vendors hit by short-term supply issues are generally optimistic. For instance, Gary Smith, Ciena’s CEO, noted last week that “Despite supply chain challenges and elongated lead times, strong secular demand trends show no signs of abating. And we remain confident that the fundamental macro drivers propelling this demand are durable over the long term.”

The biggest near-term risk to that is China’s ongoing series of COVID shutdowns. Longer term, the bigger risk is any interruption to Taiwan’s ability to continue functioning as an independent, self-governing country – it plays a key role in the telecom supply chain, and that of many other sectors. This issue is the elephant in the room that few like to address, but all vendors need to have a plan for this worst case scenario.

*

Source of cover image: iStock