After a prolonged hiatus, M&A activity in the semiconductor landscape ramped up significantly this year, nearing the record levels of 2015. The consolidation surge was particularly notable during the second half of 2020. These deals targeted many end use markets but the common thread is the cloud data center market: remote work and study amid the COVID-19 pandemic has spiked demand for cloud-based tools and services. The dealmaking is not yet done. Next year is likely to witness more consolidation among chipmakers, despite geopolitical tensions between the US and China and stringent regulatory scrutiny serving as impediments to deal completion.

Flurry of chip deals bring cheers to an otherwise muted first half

Chip M&A activity had a quiet first half of the year, as COVID-19 created high levels of uncertainty and steep drops in GDP. Stock markets settled in 2H20, though, and big companies found ways to operate amidst a pandemic. COVID-19 remains a severe problem for many major economies, but improved business sentiment and a gradual economic recovery have fostered a strong climate for M&A.

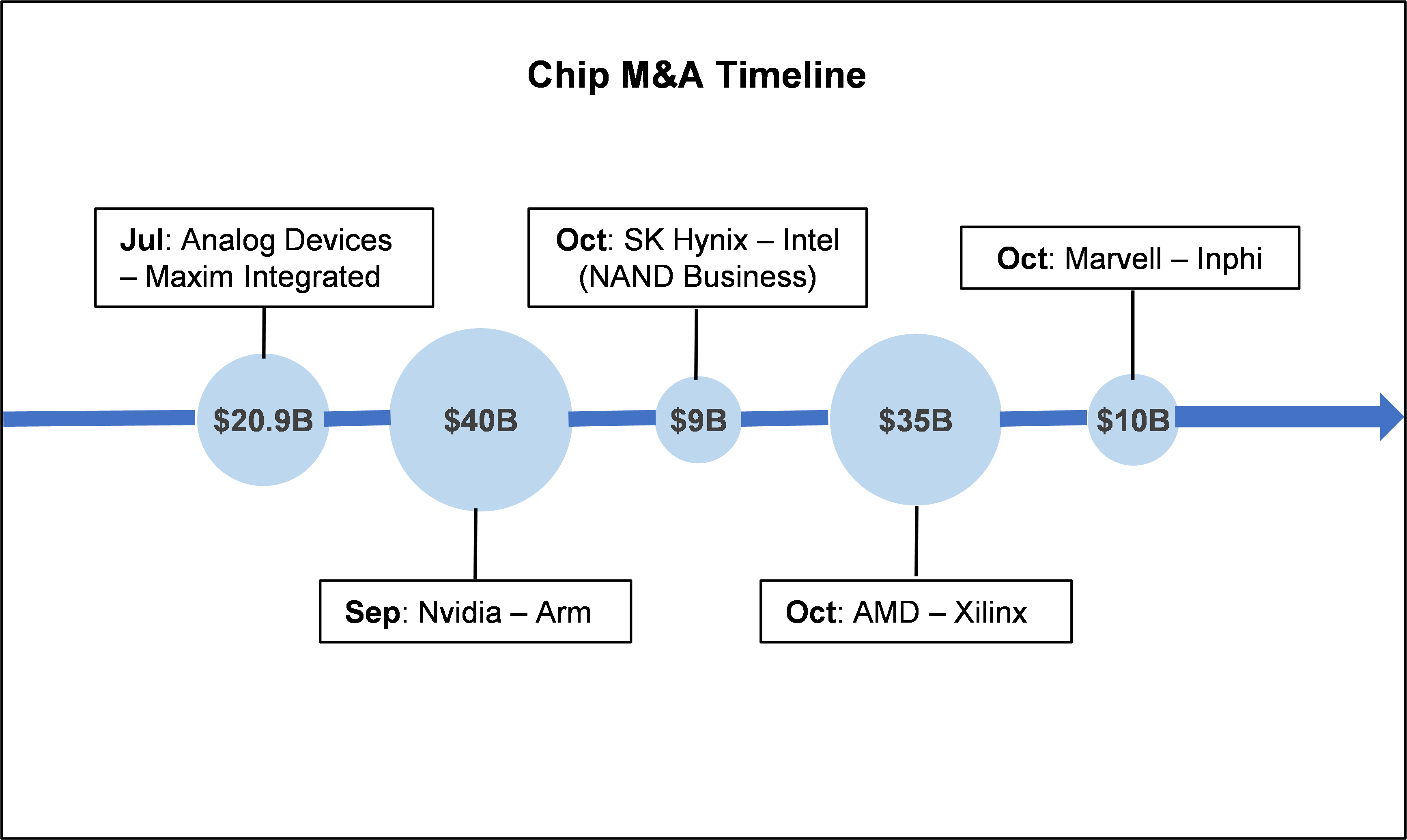

With year-to-date announced deals already topping $100B in value, 2020 is turning out to be a blockbuster year for chip M&A. The mega-deal kickstart to the chip M&A frenzy was Analog Devices’ $20.9B acquisition of rival chipmaker Maxim Integrated Products in July 2020. This was followed by Nvidia’s acquisition of chip design house Arm for $40B in September 2020, the year’s biggest deal so far. The month of October saw a string of M&A agreements featuring the $9B acquisition of Intel’s NAND SSD business by SK Hynix, AMD’s $35B deal to acquire Xilinx, and Marvell’s $10B acquisition of Inphi.

Figure 1: Timeline of semiconductor M&A in 2H20

Source: MTN Consulting

Chipmakers aim at the lucrative cloud data center market

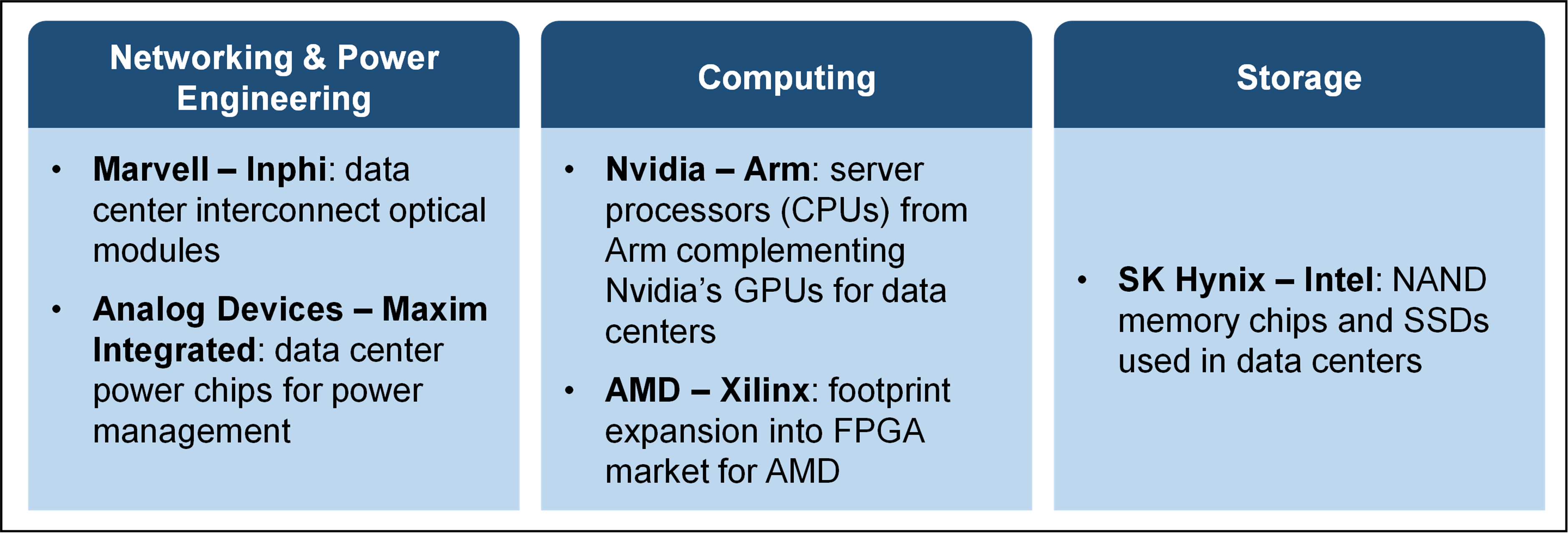

None of the big chip deals are focused narrowly on a single end market, but one key market is of common interest to all – the cloud data center. The deals differ from each other in terms of sub-market focus, though, stretching from power engineering and networking, to computing and storage – see Figure 2 below:

Figure 2: Data center aspects of 2020’s big chip M&A transactions

Source: MTN Consulting

Networking & Power Engineering

Networking and power management form the vital foundation of any data center infrastructure. Optical modules help connect not just the server racks inside data centers but also the data centers to one another across different locations. With the acquisition of Inphi, Marvell aims to target this space by providing interconnect solutions that enable seamless and speedy movement of data between and inside data centers.

Chips for power management have grown in significance over the years to control the biggest expense of running a data center, i.e. power utility costs. Analog Devices is seeking to address this issue through Maxim Integrated’s data center power chips, which also permit greater computational capability to data center operators.

Computing

Data centers typically house thousands of servers that process and run applications along with high performance computing (HPC) workloads. The processing and computational tasks are carried out by server processor chips that come in various forms: CPU, GPU, FPGA (field-programmable gate array), and ASIC (application-specific integrated circuit). Intel, AMD, Nvidia, Xilinx, and Infineon are some of the leading server processor vendors developing either one or most of the chip types.

The acquisitions announced by AMD and Nvidia relate to expansion into new server chip types, and also rivaling Intel as a more formidable force. AMD is looking to dent Intel’s customer base with the acquisition of Xilinx. The FPGA pioneer Xilinx had earlier managed to end Intel’s exclusivity with some its customers such as Microsoft. Meanwhile, GPU maker Nvidia will gain access to server CPU designs through its Arm acquisition. Arm-based server processors are already being adopted by webscalers like Amazon for its data centers. For now, Intel is looking to counter these developments through in-house efforts aimed at the server GPU market for data centers, extending its presence across all the four chip types.

Storage

On the storage side of things for data centers, Intel has agreed to sell off its NAND SSD business to SK Hynix. The assets sold include Intel’s NAND component and wafer business along with the NAND manufacturing plant in Dalian, China, but exclude Intel’s “Optane” memory business. Intel’s NAND memory chips are mostly used in smartphones but also data centers to support in-memory processing demands of the cloud. The business acquisition will elevate SK Hynix’s market share in the NAND memory market, which is currently dominated by Samsung Electronics.

Three key factors are fueling M&A among chipmakers

Three key factors discussed below are driving chip companies to go on a shopping spree:

- New applications: Key emerging applications based on AI/ML along with new evolving markets in edge computing, self-driving vehicles, and 5G have opened new frontiers for chipmakers. This is in addition to the ever-increasing demand for more media-intensive content such as images, audio, and video streaming over cloud that require faster server processors and networking capabilities for seamless and speedy transmission to end users.

- Faster time to market: Apart from the obvious reasons of expanding into new markets and accessing proprietary technologies, chipmakers are increasingly exploring M&A to cut down on the costly and lengthy R&D timeline associated with developing advanced process nodes and chips, thus enabling faster scaling. Slowdown in Moore’s law is also pushing chipmakers to look elsewhere.

- Improved market conditions: A low interest rate environment has enabled chipmakers to borrow modestly and finance acquisitions. Rising stock prices are also aiding large chipmakers such as AMD and Nvidia to fund their purchase either partially or entirely in stocks. Notably, Nvidia surpassed Intel as the largest US chipmaker by market cap in July 2020

More chip industry consolidation on cards but not without hurdles

The M&A activity in the chip market landscape is likely to continue into next year, but probably not at the scale of what has transpired so far in 2020. Even though the deal-making drivers discussed above will persist in 2021, future deals may confront more obstacles related to COVID-19 and geopolitics.

With COVID-19 expected to play out well into 2021, delays in deal-making would keep the deal volumes limited as carrying out negotiations, due-diligence, and audits would be challenging with travel restrictions and limited in-person meetings. For companies having long-term or strong working relationships with prospective acquirer or targets, the pandemic would be less of a worry, as seen with Nvidia-Arm or AMD-Xilinx for instance. These pairings shared strong working relationships prior to acquisition.

Geopolitical tensions between the US and China upsets the stability needed to make M&A deals happen. That’s especially true in the chip sector. With the situation not expected to get any better even under the Biden administration, China has been gearing towards chip self-sufficiency by pouring billions of dollars to support the growth of its domestic chip industry and advanced chip development. Furthermore, open-source chip architectures such as RISC-V have opened the gates for Chinese tech firms like Huawei. Chipmakers will be wary of snapping up companies amid a hostile business climate.

Last but not the least is the regulatory hurdle that an M&A transaction must go through before the final deal closure. Big-ticket deals are subjected to increased scrutiny due to wide-ranging issues such as strict antitrust laws, national security threats, access to proprietary technology, and sanctions imposed under trade disputes. All the chip M&A deals discussed above are pending regulatory approval, in multiple jurisdictions. Among them, the Nvidia-Arm deal is likely to raise eyebrows among the watchdogs, especially in Europe and China. China could essentially prove to be a spoilsport in the Nvidia-Arm deal: Chinese tech firms currently use UK-based Arm’s intellectual property to design chips, which could change post acquisition by US-based Nvidia. If China blocks this transaction, it would not be the first time. Two years ago, China blocked US-based Qualcomm from completing its acquisition of the Netherlands-based chipmaker NXP Semiconductors.