Prediction: India-based vendors almost certain to capture less than 4% of global telco network infrastructure market in 2021

Prospects for 2021

The year 2021 is likely to see some significant shifts in vendor share in the global market for telecom network infrastructure products & services (“Telco NI”). Spending on 5G is picking up, interest is growing in open RAN architectures (and open networking in general), telcos are making more carefully thought out decisions without the chaos of COVID-19 dominating discussions, software’s share of capex is rising, and Chinese vendors continue to face supply chain and security constraints to their global position. Many telcos, and policymakers in the US, have pointed to India as a potential alternative player in the Telco NI market. India and the US are allies, after all, and India has a program aimed at developing local manufacturing – which calls to mind similar programs in China that helped Huawei and ZTE. The question arises, then: what are the prospects for India-based vendors globally in 2021? More specifically: what is the chance that India-based vendors can grow their share of Telco NI above 4% in 2021?

After reviewing the question, our conclusion is that there is less than 10% chance of this happening. Not impossible, but nearly so. Here is our assessment of a few key issues.

Current share below 3%

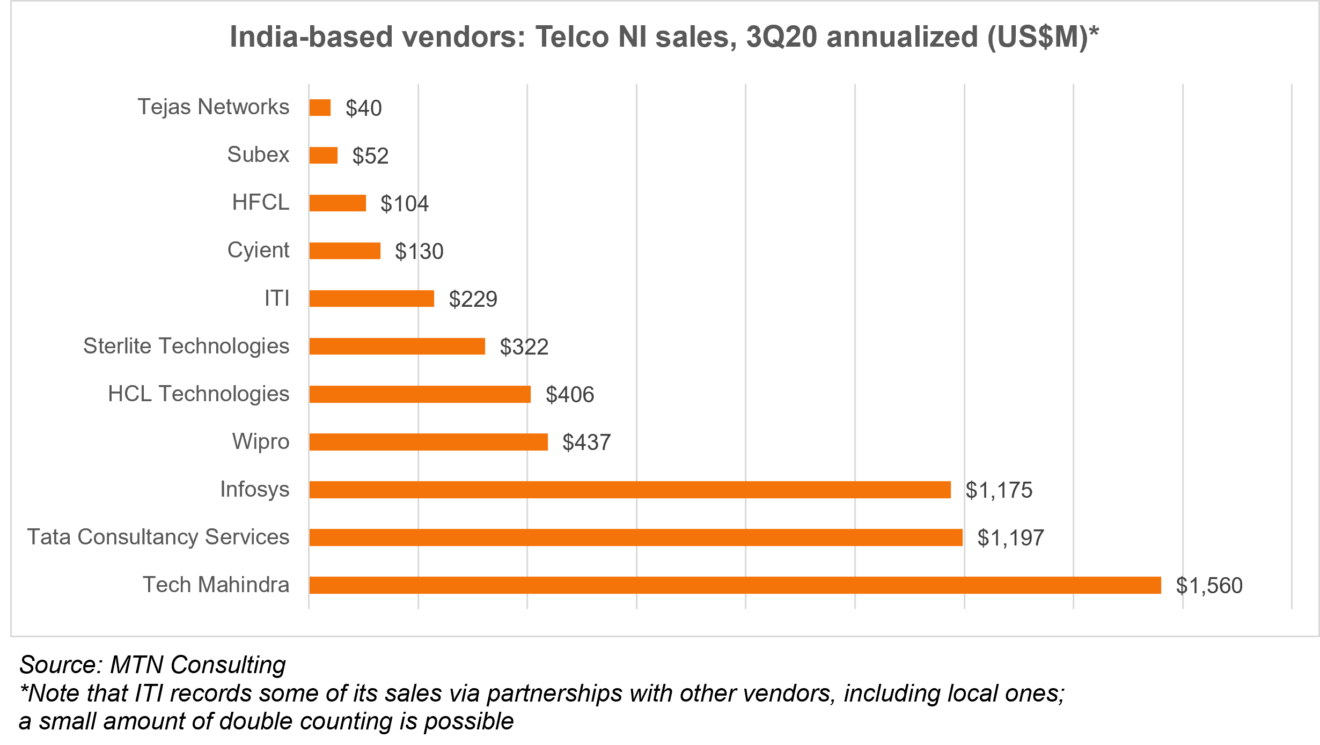

For the four quarters ended 3Q20, MTN Consulting estimates that vendors based in India captured roughly 2.6% of vendor revenues in the global telco network infrastructure (telco NI) market. That is based on sales to telcos for eight vendors we currently track (HCL, Infosys, Sterlite, Subex, TCS, Tech Mahindra, Tejas Networks, and Wipro), plus three vendors we are in the process of adding to our database: Cyient, HFCL, and ITI Limited. Annualized telco NI revenues for these 11 companies, by our estimation, amounted to $5.7 billion in 3Q20, out of a global market of $216.3 billion. Nearly 70% of that $5.7 billion is recorded by three IT services players: Infosys, TCS, and Tech Mahindra, with the latter slightly ahead of the first two. (see chart, below)

So, India’s starting point is low. Jumping from less than 3% to above 4% in the space of a few quarters is a challenge. Adding one percentage point in share is not the issue; larger vendors with the ability to ramp manufacturing to satisfy big one-time orders can do this easily. Most of India’s Telco NI strength lies in services, integration, and software development contracts, though, which tend to take more time to implement. Moreover, India is a relatively small market within global telecom. Local vendors do benefit from set-asides and easier access to local customers, but India accounted for less than 3% of global capex in the last four quarters. It has been higher in the past, in fact reaching 6.1% of global capex in the 1Q19 annualized period. But that was during Jio’s massive network buildout and aimed at helping the company jump ahead of the competition rapidly, which it succeeded in.

India’s 5G buildout will be hobbled by pricey spectrum

Last month the FCC held an auction for 5G-suitable spectrum in the US. Winning bids totaled up to just under $81 billion, a bit more than 90% of the US telco market’s total annual capex of $88B (2019). Many observers have warned that this outcome could hobble the telcos financially, as they now also need to come up with capital to deploy the networks. These concerns are well-founded.

India could be in an even more precarious situation. Its primary 5G auction won’t be held until next month, but could potentially raise up to $50B or more for the Indian state treasury. This figure is several times India’s 2019 telco capex figure of $10.9B.

Contrast this with China’s approach, where spectrum is generally given away for free (or nearly so), and the government uses its control of key operators to drive procurement practices and the pace of deployment. Because of this, 5G in China is seeing rapid adoption and local vendors have benefited massively. Huawei and ZTE gained share last year in the Telco NI market, in fact, despite all of their problems.

A slow 5G rollout in India means fewer opportunities for local vendors to win new deals and gain crucial experience that they could leverage in global markets.

State-run operators are small and procurement is slow

One area where India’s vendors clearly shine is with state-run operators BSNL and MTNL. Government procurement rules favor local suppliers strongly. However, the two together accounted for just $614M in 2019 capex, under 6% of India’s total. Further, the hoops they must jump through to build new network projects are cumbersome. Disputes about winners and losers can slow down final decisions and the actual spending connected to the decision.

BSNL’s long-planned 4G tender is a good example. It’s now more than 4 years since Jio debuted its 4G network in 2016, and BSNL is still at the early procurement stage with 4G. The project has been delayed several times. Most recently, BSNL did issue an expression of interest document covering a potential network with 57,000 sites. As promising as that sounds, it remains unclear what it means to be local. Partnering with a foreign vendor such as Samsung or Ericsson might qualify; having a large R&D presence in India (e.g. Mavenir) might also allow one to slip through. The challenge is that there does not exist a truly Indian company able to build a 4G network end-to-end, and it cannot be created overnight.

Hiring a truly Indian services firm like Tech Mahindra is one option for BSNL, as TM can get more experience putting together the piece parts for a network in way that will help with Open RAN opportunities. Tech Mahindra already works with Telefonica and Rakuten on Open RAN.

Jio succeeded while avoiding local NI vendors

Indian telecom’s big success story in recent years is clearly that of Jio Platforms, which emerged from little in 2016 to become the market’s largest wireless provider in just over three years. Jio did many things differently than its rivals, one of which was to rely almost entirely on foreign vendors – but avoiding the Chinese. Jio has some gear from Tejas in its network and a few other small local vendors, but it’s minimal given the telco’s size. There is no current sign to suggest Jio will be more eager to adopt local tech as part of a future 5G rollout. If spectrum was to be issued on a cheaper (or even free) basis but come with some ‘buy local’ requirements, clearly the outcome would differ.

Bharatnet is not that big a project in global terms

India has made impressive strides in expanding connectivity in rural regions over the last few years, due largely to the Bharat Broadband Network, or Bharatnet. This project has been especially helpful to local fiber manufacturers. It continues, but the scope of the project needs context. For the fiscal year 2020-21, approximately $800M was budgeted for Bharatnet. That is a sizable amount, and many local vendors (e.g. Tejas) cite national or state-level Bharatnet projects as contributing to recent revenue growth. But $800M works out to roughly 2% of telco industry capex in China alone for 2019. The project is just not big enough to help a local vendor go global.

What could swing things the other way?

In my opinion, it would be great to see a globally competitive vendor emerge from India. At one point in the distant past, it seemed that Tejas had potential to be a real player in the optical market. That has not happened; lack of a local supply chain and manufacturing are among the many issues.

Currently Tech Mahindra is looking like it has real potential, with a growing focus on the blossoming Open RAN market, and helping telcos integrate these new networks. Tech Mahindra’s collaboration with Rakuten on this point is promising. TM will have competition from many other companies going after these projects, though – not just RAN vendors but other telcos, including NTT DoCoMo. It’s not just Tech Mahindra with potential, though; Infosys, TCS, and Wipro are already active in 5G RAN networks. If these IT services specialists can quickly help telcos review and implement new network architectures that have verifiable cost savings, then India’s vendor prospects may brighten.

The biggest thing that could support the local industry, though, is a different government philosophy on spectrum auctions. Clearly the government needs to raise funds to operate, and auctions are one easy way. But if there is interest in developing local 5G ecosystems and helping local companies make it big globally, then maximizing auction proceeds cannot be the overriding goal.