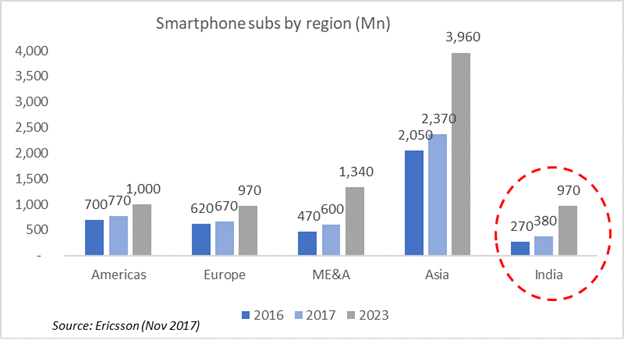

Optimistic 5G forecasts assume that telcos’ spectrum needs are met

Ericsson recently predicted that by 2024 5G subscriptions will reach 1.9 billion, 35 percent of traffic will be carried by 5G networks and up to 65 percent of the global population could be covered by 5G. This is one of the many forecasts that predict the success of 5G, however there are many variables attached to it. A key one is the availability of suitable, affordable and importantly harmonized radio frequency spectrum, which is the focus of this blog.

Harmonized spectrum is key for 5G success

At the upcoming World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC), the overall goal of the telecommunication world at is to secure a sizeable chunk of harmonized spectrum for 5G.

Spectrum harmonization drives economies of scale, better battery life (as phones don’t need multiple radio modules and to toggle between frequencies), less cumbersome roaming and lesser cross border interference. It’s essential for 5G to succeed.

Government policymakers want to auction or license this harmonized spectrum to cover their current and future budgets. Telecom network operators on the other hand are interested in getting this harmonized band(s) at a reasonable cost from governments in order to meet operational excellence requirements and achieve their business targets in partnership with their vendors.

Background on spectrum

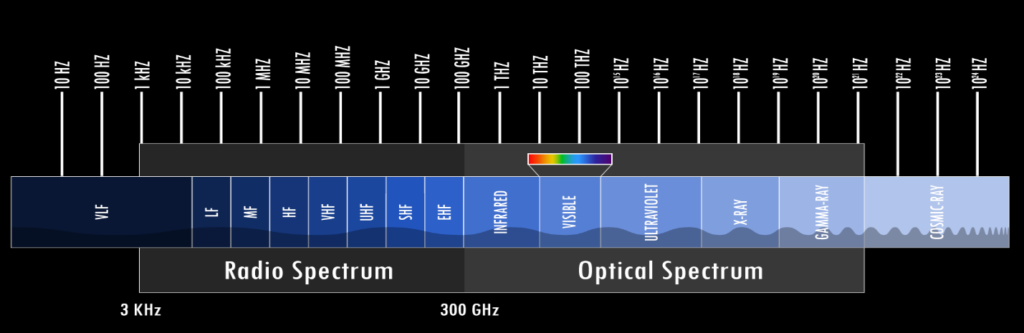

Wireless communications require airwaves to provide services. Airwaves, or electromagnetic spectrum, consist of a range of all types of electromagnetic radiation, from radio waves to gamma rays. The range of frequencies that are used for providing mobile and WiFi connectivity falls under the radio frequency (RF) portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. RF spectrum ranges from 3 kHz to 300 GHz (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Range of frequencies in wireless communications

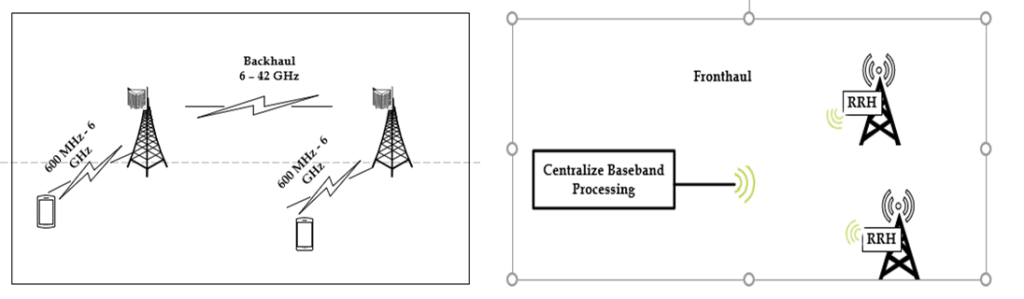

Mobile communications – a subset of wireless communications – primarily takes place in the range of 600 MHz to 42 GHz. The lower frequency bands are suitable for addressing communications between mobile phones and base stations (radio towers) while the high bands are used for supporting backhaul connectivity between radio towers. Fronthaul, which is a much newer concept, connects remote radio heads mounted on towers to baseband units located in a centralized location. Fronthaul requires much higher bandwidth and minimal latency and thus for the most part it is supported with optical fiber. However, in case fiber is not available, a wireless medium can be used (e.g. microwave). (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Use of radio waves in cellular networks

The electromagnetic spectrum requires proper management, allocation, assignment and harmonization at a global level. That’s because wireless communications isn’t limited by national boundaries, and a global approach helps facilitate economies of scale. This huge function is performed by the ITU (International Telecommunication Union), which is the United Nations’ specialized agency covering information and communication technologies (ICTs). More specifically, the ITU’s Radiocommunication sector (ITU-R) takes care of this obligation at the global level.

ITU-R allocates spectrum through the pivotal World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC), which takes place once every 3-4 years. WRC is the most significant inter-governmental event related to the frequency spectrum. WRC has a mandate to review, and, if necessary, revise global Radio Regulations, the international treaty governing the use of the radio-frequency spectrum and the geostationary-satellite and non-geostationary-satellite orbits. This treaty is the basis for the harmonization of spectrum worldwide.

WRC allocates frequencies to everything that needs airwaves for execution – from as small as garage door openers all the way to space satellites, and everything in between (terrestrial, aviation, maritime, etc.).

Once spectrum is allocated at the WRC, national regulatory bodies such as the FCC and can assign specific bands to specific service providers (such as AT&T, Sprint, etc.) through a license for a specific number of years.

To predict the future, you have to understand the past

The focus of this blog is three-fold: (a) to provide a brief summary of the key activities that took place at WRC-15 (b) to give a sneak preview of the upcoming WRC-19 and (c) to analyze the cost and global implications of spectrum for 5G.

Recap from WRC-15

The demand for wireless connectivity and applications on the go is continuously on the rise. The wireless industry requires quick access to frequency spectrum and a lot of it, on a worldwide basis. Back in 2014, the ITU-R predicted that the world would need an additional 1340-1960 MHz for broadband services by 2020. The aim of the world body was to get harmonized spectrum in the range suggested by ITU-R, preferably on a global scale, if not then at least to some extent on the regional basis.

To keep the story short, WRC-15 can be considered as the first major international event that looked into allocating frequency spectrum for 5G. However due to some geopolitical challenges and presence of many existing services, the WRC-15 was only able to allocate 51 MHz for IMT (International Mobile Telecommunications) systems on the worldwide basis. In addition to this 51 MHz allocation which was made in the L-band (1-2 GHz), sizeable additional allocations were made on a regional basis. The total allocation was over 1500 MHz, satisfying the regional requirements for the most part (Table 1).

To clarify, IMT is the flagship project of the ITU-R and covers 3G, 4G and 5G systems. The ITU-R doesn’t allocate spectrum for a specific mobile generation but rather in generic terms of MOBILE and IMT. This capitalization means that the service has been allocated on a primary basis and no other service can interfere in its operations.

In the past, the identification of spectrum as MOBILE for cellular/broadband systems (including 2G) was sufficient. However, the advent of 4G/5G has the brought the concept of IMT systems to the limelight and now even if a service is already allocated for MOBILE, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it can be used for it unless it has been identified as IMT in the footnotes.

Table 1: IMT allocation at WRC-15

| Band (MHz) | Regions (or parts thereof) * | Bandwidth (MHz) |

| 450-470 | 2 | 20 |

| 470-698 | 2 & 3 | 228 |

| 694/698-960 | 1, 2 & 3 (not worldwide) | 262 |

| 1427-1452 | Worldwide | 25 |

| 1452-1492 | 2 & 3 | 40 |

| 1492-1518 | Worldwide | 26 |

| 1710-2025 | 2 | 315 |

| 2110-2200 | 2 | 90 |

| 2300-2400 | 2 | 100 |

| 2500-2690 | 2 | 190 |

| 3300-3400 | 1, 2 & 3 (not worldwide) | 100 |

| 3400-3600 | 1, 2 & 3 (not worldwide) | 200 |

| 3600-3700 | 2 | 100 |

| 4800-4990 | 2 & 3 | 190 |

Sources: 5G Mobile Communications: Concepts and Technologies, and the ITU.

*Region 1 comprises of Europe, Africa, the former Soviet Union, Mongolia, and the Middle East west of the Persian Gulf, including Iraq. Region 2 includes Americas including Greenland, and some of the eastern Pacific Islands. Region 3 covers non-FSU (former Soviet Union) east of and including Iran, and most of Oceania.

WRC-15 also identified several bands as study items for their potential usage for IMT. The range covers various bands from 24.25 GHz to 86 GHz. These bands are already providing a number of services particularly backhaul and satellite. The specific services in these bands also can differ by region to some degree. Therefore, spectrum sharing and compatibility studies were required to look at their applicability of co-existence with IMT.

WRC-19 Preview

Before diving into WRC-19 it is worthwhile to look into the work executed by 3GPP in this regard after WRC-15. 3GPP, the flagship organization for 4G and 5G specifications, identified the following two frequency ranges:

- Frequency Range 1 (FR1): 410 MHz to 6000 MHz with channel bandwidths in the range of 5 to 100 MHz with increments of either 5 or 10 MHz. This frequency range is applicable for both frequency and time division multiplexing modes.

- Frequency Range 2 (FR2): 24.25 GHz to 52.60 GHz with channel bandwidths of 50, 100, 200 and 400 MHz supporting operations only in time division multiplexing mode.

3GPP focuses more on the nitty gritty of spectrum which has been identified in broad terms by ITU-R. 3GPP works more on the lines of identifying channel bandwidths and duplexing modes to support the underlying mobile services.

In preparations for WRC-19, the ITU-R as per its practice executed the two Conference Preparatory Meeting (CPM) sessions. In February 2019, the ITU-R issued a close to 1,000-page “CPM 19-2” report, designed to assist in preparations for and deliberations at WRC-19. It can be said that hundreds of resources, thousands of workforce hours and millions of dollars have been spent to study the subject frequency range.

The upcoming WRC-19, scheduled to take place later this quarter, has two major tasks when it comes to the allocation for MOBILE/IMT.

First to conclude on the applicability of the identified bands for MOBILE / IMT as required by agenda item 1.13 (Table 2). The CPM 19-2 report forecasted that IMT will require 0.33 GHz to 12 GHz of spectrum in the ranges of 24.25-33.4 GHz, 37-52.6 GHz and 66-86 GHz, depending upon the metrics, assumptions and frequency range. The problem is that all the bands listed in Table 2 are already in use. Further identification for IMT on a primary basis could face stiff opposition particularly from the satellite community at the WRC-19. Opposition from satellite is even more an issue than 2015 as many new players have entered this space, including some deep-pocketed companies like Amazon and Facebook.

Table 2: Applicability of identified bands for MOBILE/IMT (WRC-19 conference prep, Agenda item 1.13)

| Band (GHz) | Bandwidth (GHz) | Key Current Primary Allocation Services | Potential Additional Services |

| 24.25 – 27.5 | 3.25 | FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE,

EARTH EXPLORATION-SATELLITE, MOBILE, INTER-SATELLITE |

Identified by CPM to be used for IMT |

| 31.8 – 33.4 | 1.6 | FIXED, INTER-SATELLITE, SPACE RESEARCH, RADIONAVIGATION | Has not been identified by CPM for IMT |

| 37 – 40.5 | 3.5 | FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE, SPACE RESEARCH, MOBILE, MOBILE-SATELLITE | Identified by CPM to be used for IMT . |

| 40.5 – 43.5 | 3.0

|

FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE, BROADCASTING, BROADCASTING-SATELLITE | Identified by CPM to be used for IMT |

| 45.5 – 50.2

|

4.7

|

FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE, MOBILE | Identified by CPM to be used for IMT |

| 50.4 – 52.6

|

2.2

|

FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE | Identified by CPM to be used for IMT |

| 66-76

|

10 | FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE, BROADCASTING-SATELLITE, MOBILE, MOBILE-SATELLITE, RADIONAVIGATION, RADIONAVIGATION-SATELLITE | Identified by CPM to be used for IMT |

| 81-86 | 5 | FIXED, FIXED-SATELLITE | Identified by CPM to be used for IMT |

Source: ITU (https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-r/opb/act/R-ACT-WRC.12-2015-PDF-E.pdf, and https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-r/opb/act/R-ACT-CPM-2019-PDF-E.pdf)

Second, WRC-19 will need to look into spectrum allocation issues affecting several other big markets as listed in agenda items 1.11, 1.12, 1.14 and 1.16 and their implications on existing and future IMT systems:

- Railway radiocommunication systems between train and trackside within existing mobile service allocations – RSTT

- Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) under existing mobile-service allocations

- High-altitude Platform Stations (HAPS), within existing fixed-service allocations, and

- Radio local area networks (RLAN), in the frequency bands between 5.150 GHz and 5.925 GHz

A brief summary of the key bands under consideration for these services is provided in Table 3 below. There are several bands that are already in use for IMT and thus any allocation to any new service needs to be justified and obtain consensus from administrators.

Table 3: Key bands for RSST, ITS, HAPS & WLAN

| Potential Service | Key Bands Under Consideration |

| RSST | 138-174, 335.4-470, 703-748, 758-803, 873-925, 918-960, and 1770-1880 MHz; 43.5-45.592 GHz and 92-109.5 GHz |

| ITS | 5850-5925 MHz |

| HAPS | 6.44-6.52, 21.4-22, 24.25-27.5, 27.9-28.2, 31-31.3, 38-39.5, 47.2-47.5 and 47.9-48.2 GHz |

| RLAN | 5150 – 5925 MHz |

Source: MTN Consulting

Big battles lie ahead

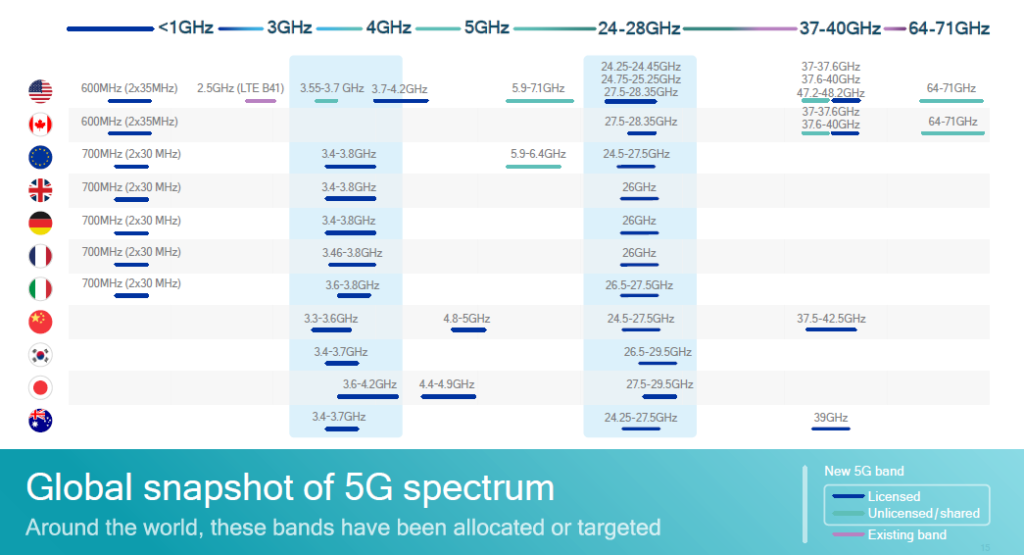

At this stage, the telecom industry is not close to achieving its target of harmonized, adequate 5G spectrum resources. Basically, there are two camps – one is favored by China and other by the USA. Disagreements are not settled easily at this stage as there is a first mover advantage in the development of mobile wireless generations. The market leader can set the stage for future infrastructure development, product development and specifications. In this context, three ranges of spectrum bands have been considered namely:

• low band (sub 1 GHz) which is used heavily for broadcasting and wireless services.

• mid band (1 GHz to 6 GHz) which is primarily used for wireless services.

• millimeter wave or mmWave (24 GHz to 100 GHz) which is used for many non-mobile services (Table 2)

The battle hovers around the sub 6 GHz and mmWave bands. China is looking towards 3.5 GHz whereas the USA is focusing on multiple millimeter bands. The mid band, particularly the 3.5 GHz band that ranges from 3.3 to 3.8 GHz, is the most sought after band for use as a core band for 5G. That’s because of this band’s availability and lower deployment costs as compared to mmWave bands. China already assigned 200 MHz in this mid band. By contrast Japan and South Korea are working in both mid and mmWave bands. The rest of the world for the most part is playing catch-up on 5G spectrum assignments (Figure 3)

Figure 3: 5G spectrum bands by region

The US faces a unique problem in the mid-band. Namely, the US Department of Defense currently holds roughly 500 MHz in the 4 GHz range and thus it cannot be used for commercial operations. According to a DoD report, the estimated time required to clear spectrum (relocate existing users and systems to other parts of the spectrum) and then release it to the civil sector, either through auction, direct assignment, or other methods could take 10 years. Spectrum sharing between entities is another option and is a slightly faster process, but it could still take five years according to the same DoD report. Thus, the FCC has focused on the mmWave band. It had to auction out 24 GHz and 28 GHz bands and is planning to offer 37, 39 and 47 bands as well in the future. This is one of the key factors behind the limited coverage launches of 5G in USA. Verizon’s 5G network is based on the 28 GHz and 39 GHz bands, AT&T uses 39 GHz, and T-Mobile is planning 28 GHz. Sprint is eyeing the 2.5 GHz band as it doesn’t have any spectrum assets in the mmWave range.

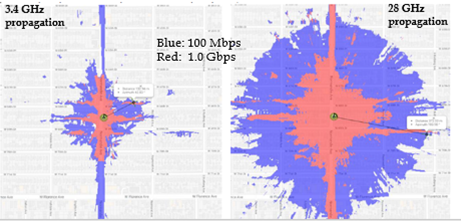

A study conducted by Google for DoD found severe limitations in the mmWave band. It concluded that for the same number of cell sites (macro cell sites and rooftops), 1 Gbps can only be provided to 3.9% coverage area at 28 GHz (US model) as compared to 21.2% at 3.4 GHz (Chinese model). The same study also estimated that it will require approximately 13 million utility pole-mounted 28-GHz base stations (one of the key choices of US operators for mmWave) and $400B in capex to deliver 100 Mbps edge rate at 28 GHz to 72% of the U.S. population, and up to 1 Gbps to approximately 55% of the U.S. population. Figure 4 illustrates the problem, showing the propagation difference between 28 GHz and 3.4 GHz deployments on the same pole height in a relatively flat part of Los Angeles.

Figure 4: Propagation difference in Los Angeles: 28GHz vs 3.4GHz

In a nutshell, mmWave bands will likely have a detrimental impact on operators’ budgets, at a time when they are not eager to ramp up capex. At the end of 2018, Verizon held ~$120B in debt with ~4% dividend yields, while AT&T held ~$175B in debt with over 6% dividend yields. T-Mobile holds ~$25B in debt, and Sprint holds ~$40B in debt. These companies are at the forefront of the U.S. effort to develop 5G, but their balance sheets suggest that they may struggle with the cost of a full mmWave network roll-out and the infrastructure it would require.

Conclusion

The wireless world’s technology leadership role will be at stake at WRC-19. History has proven that having access to the right set of spectrum assets can deliver a competitive advantage in the overall supply chain for years to come. The implications are vast both from the commercial and strategic point of views, impacting governments, operators, vendors, and ultimately jobs.

As of today, the industry lacks harmonized frequency bands for 5G. Perhaps at the end of WRC-19 the world will be closer to achieving this goal.

Stay tuned for more news from MTN Consulting on RF Spectrum and WRC-19!

–

*Saad Asif is a Contributing Analyst for MTN Consulting and a recognized industry expert in wireless communications. He has worked in the field of telecommunication for over 21 years, and has authored three books and multiple peer-reviewed technical papers. Saad has been granted multiple patents and is a senior member of the IEEE.