Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous country, is expected to face an uphill battle to enable 5G. Reasons include its complex geography, unavailability of core 5G frequency band (i.e. C-band 3.3 to 4.2 GHz), and dwindling operator revenues. The goal of this post is to briefly address these challenges and make suggestions for how to improve 5G’s outlook in the country.

| Recommendations |

|

There are several steps that would improve the outlook for 5G in Indonesia. The Ministry of Communication and Informatics (MCI) may: • take steps to make the 3.3-3.4 GHz band available for International Mobile Telecommunication (IMT); Meanwhile Indonesia’s operators should utilize the connectivity provided by the recently completed Palapa Ring project to expand their business in remote areas, and work with MCI for an effective market consolidation. |

Indonesia overview

Indonesia, home to over 271 million people, is an island country in Southeast Asia comprised of more than 17,000 islands. It is the world’s 4th most populated country with the world’s 16th largest economy in terms of nominal GDP (gross domestic product).

Indonesia shares land borders with Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste, and the eastern part of Malaysia. Australia, India, Palau, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam are its maritime neighbors (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Indonesia Map

Telecom market overview

Government

Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Informatics is responsible for organizing government policy in the field of Information and Communications Technology. In 2003, the Ministry established the Indonesian Telecommunications Regulatory Body (BRTI) to which it delegates authority to regulate, supervise and control telecommunications networks and services. BRTI is also responsible for executing frequency spectrum auctions.

Mobile operators

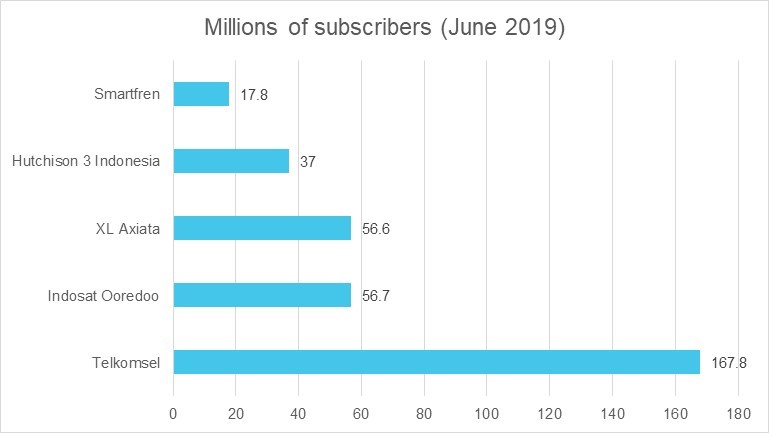

Indonesia is the fourth largest cellular market in the world with more than 330 million subscribers. The market is dominated by five cellular players, including state-owned Telkomsel and privately held Indosat Ooredoo, Hutchison 3 Indonesia, XL Axiata, and Smartfren. (Figure 2) SingTel has a 35% stake in Telkomsel, with the remainder held by incumbent Telkom Indonesia.

2G (GSM/GPRS) is still the dominant technology with close to 45% of subscriptions. Mobile broadband comprised of 3G and 4G networks has made substantial progress since inception. Operators continue to expand 4G network coverage to remote areas. For example, Telkomsel deployed 22,000 4G LTE base stations in its network between January and September of 2019, stretching deeper into rural regions.

Figure 2: Mobile subscriber totals for Indonesian telcos, June 2019 (millions)

Although 5G is making headlines globally, Indonesia’s operators are not in a rush to deploy as they continue to expand 4G penetration and await a settlement between the US government and Chinese vendors, and perhaps for market consolidation.

The Ministry is in favor of consolidation due to declining financial health of the operators. As in most countries, telcos in Indonesia are not finding topline growth easy to achieve. Market leader Telkom Indonesia, for instance, has faced negative revenue growth rates over the last few quarters, in USD terms (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Annualized revenue growth rate for Telkom Indonesia (YoY % change), USD-basis

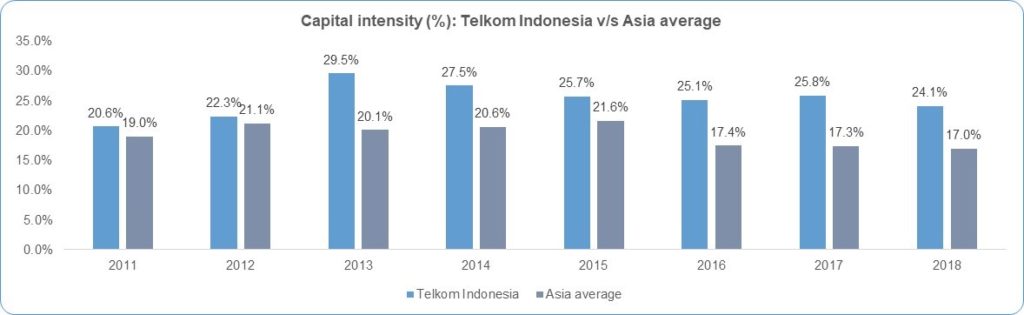

If measured in local currency, Telkom’s revenue growth rates are slightly better than the above figure. A weakening currency has worsened the comparisons. Currency issues have also made imported network equipment more expensive recently, a big issue in Indonesia where capex to revenue ratios are often well above 20%.

Independent tower operators

To help cope with high network costs, operators in Indonesia have transferred the bulk of their radio tower business to third parties (tower companies). Indonesia’s five big tower companies ended June 2019 with control of 45.3K towers, up from 42.5K in June 2018. Tower spinoffs continue. For example, Indosat Ooredoo recently agreed to sell as many as 3,100 telecommunication towers to local tower providers. PT Daya partner Telekomunikasi (Mitratel) will buy 2,100 of Indosat’s towers while PT Professional Telekomunikasi Indonesia (Protelindo) will acquire 1,000 with a total transaction value of about US$456 million.

This asset restructuring has helped Indonesian telcos lower their cost base and accelerate service coverage. It has also created a viable new industry of asset specialists, classified by MTN Consulting in its global research as “carrier-neutral network operators” (CNNOs). The largest of the group, Sarana Menara Nusantara, had total 2018 revenues of $412M, about 4% of the $9.2B booked by the largest local telco, Telkom Indonesia.

Spectrum

In 2015, the Ministry allocated an additional 246 MHz of radio frequency spectrum for mobile broadband purposes. The target allocation is 350 MHz according to the Ministry’s 2015-2019 Strategic Plan. These spectrum assignments have been made through various methods including auction, refarming, reallocation, etc. Indonesia’s mobile service providers are operating in various bands now, including 450, 800, 900, 1800, 2100 and 2300 MHz (Table 1).

Table 1: Operating frequency and bandwidth allotted (MHz)

| Company | 450 | 800 | 900 | 1800 | 2100 | 2300 | Total |

| H3I | 20 | 30 | 50 | ||||

| Indosat | 25 | 40 | 30 | 95 | |||

| STI | 15 | 15 | |||||

| Smartfren | 22 | 22 | |||||

| Smarttel | 30 | 30 | |||||

| Telkomsel | 30 | 45 | 30 | 30 | 135 | ||

| XL Axiata | 15 | 45 | 30 | 90 | |||

| Total bandwidth | 15 | 22 | 70 | 150 | 120 | 60 | 437 |

Source: “Analysis of 5G Band Candidates for Initial Deployment in Indonesia,” 2018, by Septi Andi Ekawibowo, Muhammad Putra Pamungkas, and Rifqy Hakimi of the Bandung Institute of Technology (page 3)

Note: PT Sampoerna Telekomunikasi Indonesia (STI, or “Net1”) is a regional operator which started operations in 2018. It utilizes the 450 MHz frequency band to offer 4G LTE.

While the Ministry hasn’t explicitly addressed spectrum allocations suitable for 5G, it is trying to free up spectrum. For instance: digitalization of television broadcasting: The ministry is taking steps to free up spectrum by switching off analog broadcasting in consultation with other stakeholders.

Fixed line

The fixed-line segment is quite small as compared to wireless telephony market due to complex national geography, high up-front cost and operational expenses. The state-owned Telekom has the monopoly in this segment, while Indosat is the second major player, both providing services mainly in the urban areas. There are a number of alternative broadband providers and ISPs which also invest in network infrastructure locally.

Vendors

Chinese suppliers are stronger than usual in Indonesia, but Huawei, ZTE, Ericsson and Nokia all have significant shares of the local network infrastructure market. That includes 4G, and will likely extend to 5G. Just recently, ZTE signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Telkom to deploy 5G, while Nokia executed the first 5G millimeter wave network trial with Hutchison 3 Indonesia.

Geographic challenges

Development of infrastructure to provide ICT (Information and Communications Technology) services including broadband is a unique challenge due to Indonesia’s complex geography consisting of many remote islands and rural regions. Land-based connectivity is cumbersome due to oceanic separation between islands and between smaller islands to major cities, which are in some cases 1,000s of miles away. For example, the distance between Jakarta (capital of Indonesia) and Kupang (capital and major port of Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara), is 1,023 nautical miles. Thus, in many cases the preferred methods to provide connectivity include satellites, microwave radios and submarine fiber optic cable.

Due in part to its geography and disperse population, operators require higher capital investments than many other markets. For example, the capital spending of Telkom Indonesia has been higher than the Asia average consistently since 2011 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Telkom Indonesia capex/revenues vs. Asia average, 2011-18

Satellite-based Communications: Indonesia launched its own domestic satellite system in mid-1970s. The largest segment of the satellite telecom market is the backhaul connectivity followed by Internet communications for the consumers. However, only a small portion of total traffic is carried over the satellites.

Submarine Cable based Communications: Indonesia is lagging behind to some extent when it comes to providing international connectivity through submarine cables. Recent investments in new cables will help. For example, the SEA-ME-WE 3 (South East Asia – Middle East – Western Europe 3) lands in the Indonesian cities of Jakarta and Medan. Connectivity has been further improved with SEA-ME-WE 5, which was inaugurated in 2017. The SEA-ME-WE 5 cable lands in the Indonesian cities of Medan and Dumai. A number of other smaller cables connect the Indonesian market to Australia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. New projects like INDIGO and the Australia-Singapore cable will help Indonesia as well.

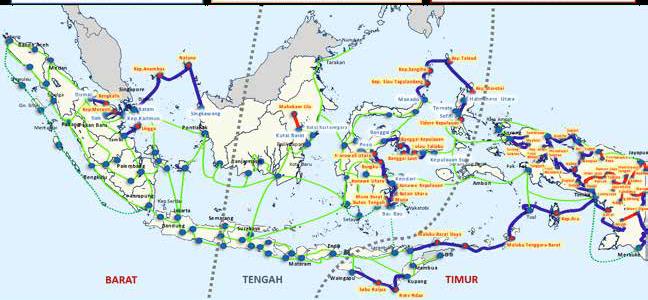

Palapa Ring Project

The Ministry has taken multiple large-scale infrastructure development projects to overcome the digital divide. One key project is the Palapa Ring network, a new national backbone network utilizing a mix of submarine and terrestrial routes. Completed in October 2019, this project took several years and $1.3B to complete. This new fiber optic backbone can be used by operators to provide broadband services. Figure 5 illustrates the Palapa project, using blue lines for fiber and blue dots for optical nodes.

Figure 5: Scope of Palapa Ring Project

Recommendations

Indonesia was ranked 111th out of 176 countries in the ITU’s 2017 ICT Development Index. This index measures the levels of economics, prosperity, literacy and other skills that enable citizens to take full advantage of ICTs. Much can be done to improve the ICT status of Indonesia, and telecommunications has a role to play.

5G could be one of the key enablers to improve the ICT standing of the country. To enable 5G, though, Indonesia at least needs a long-term roadmap, a solid fiber optic cable network, effective frequency spectrum auction(s) and a strategy for market consolidation.

The development of some of the pieces of this puzzle are still in the rudimentary stage and more concrete steps are needed. Our recommendations for further progress are as follows:

Long-term policy roadmap: Indonesia’s telecom Ministry (MCI) may need a long term roadmap for development of the sector, with three prongs. One to solve the technicalities (e.g. spectrum allocation); another to ensure an opportunity for effective return on investment; and thirdly and most importantly its benefits and implications for the people of Indonesia. With strong policy coordination, the government can use 5G as an enabler to reduce the broadband connectivity gap between its rich and poorest regions, create jobs and strengthen its ICT standing in the world.

Market Consolidation: Many successful markets have 3 to 4 cellular providers; Indonesia has five operators. Consolidation should help strengthen the dwindling financial strength of these companies. Out of the five operators, only Telkomsel has an EBITDA of 50 percent whereas Indosat, XL Axiata and Smartfren all suffered losses in 2018.

Frequency Spectrum: in Indonesia, the 5G core spectrum band of 3.5 GHz (i.e. 3.3 – 3.8 GHz) and frequencies up to 4.2 GHz are currently used for fixed satellite service (FSS) applications. FSS applications include tv broadcasting, banking communications, and Internet connectivity. In more granular terms, the range from 3.3 to 3.4 GHz is used for fixed wireless broadband and rest for FSS. FSS is extensively used in this particular band and thus to use this band for 5G will be a daunting task. Indonesia may reflect its intention for the future use of this band for mobile and more specifically for IMT (International Mobile Telecommunication) in the footnotes in the coming WRC-19.

As the availability of the core band is next to impossible in the near future, it is important to pay more attention to millimeter wave band frequencies. The recent completion of the live 5G trial in 28 GHz using Nokia’s equipment on Hutchison 3 Indonesia network is a good step. Along similar lines, ZTE and Smartfren have also conducted an indoor 5G trial on 28 GHz.

Spectrum Auctions: Spectrum auctions for 5G particularly for the core band need to be executed by keeping a strong balance between the wish-list of the government and desires of the operators. There is no magic figure for the base price of a particular frequency band, which depends on a number of variables. However, it should be lower for millimeter wave bands as compared to the core band due to much higher implementation costs of the former.

Connectivity: A solid transport network including backhaul is a must for the success of broadband and 5G. The Palapa Ring project and ongoing investments by local CNNOs and telcos will both boost the development and implementation of 5G.

–

*Saad Asif is a Contributing Analyst for MTN Consulting and a recognized industry expert in wireless communications. He has worked in the field of telecommunication for over 21 years, and has authored three books and multiple peer-reviewed technical papers. Saad has been granted multiple patents and is a senior member of the IEEE.

–

Photo by Ikhsan Assidiqie on Unsplash